Great Expectations Emigrant Governesses in Colonial Australia by Patricia Clarke

Teach your protégées to emigrate; send them where the men want wives, the mothers want governesses

For educated middle-class women in nineteenth-century Britain, options were limited. Marry and bear children, accept the drudgery of keeping house for relatives or friends, or attempt to find a position in one of the very few industries that would employ women. This is the story of a group of intrepid ladies who found a different solution on the other side of the world.

Wanted, a Governess competent to teach music, dancing, and the usual branches of education. Respectable references required.

The Female Middle Class Emigration Society scheme helped governesses and would-be governesses emigrate to the colonies from 1861 to 1886. The women who participated were encouraged to write back to the society, and it is their letters—sometimes plaintive, sometimes upbeat—that form the heart of this book. Written by women who were often fluent in multiple foreign languages, skilled artists and musicians, able to teach the liberal arts, as well as algebra and geometry, the letters describe wildly different experiences and stories of culture clash abound.

In my new home I shall make acquaintance with a new class of people—the nouveaux riches, but I may consider myself now colonized

Some women gained employment with well-established families even before their ships had docked, formed close relationships with their employers or found husbands. Dublin-born Mary Bayly had a heavy workload teaching the six Hills children of Cooks River, New South Wales, English, French, German, Latin, music and singing, but her employers were ‘very kind’, she found the Australian scenery beautiful—‘As to the Harbour and the views over the sea, they can never to me lose their charming freshness and attractiveness’—and she eventually married an Australian-born teacher who would rise to the position of headmaster, thereby retaining her middle-class status.

Be sensible, undergo a little domestic training and come out here to take your chance

Some women battled extreme loneliness, wild colonial boys and girls, unsupportive employers, poverty and disillusionment. Rosa Phayne, daughter of an accountant, considered her fellow ship passengers ‘so very low and horrid a set’, described Melbourne as ‘beyond anything abominable in every respect’ and, despite finding a position on a sheep station in the Victorian Wimmera, wrote that her employer had ‘not one feeling like a lady, although one ostensibly’ and declared life in Australia for a governess one of ‘intense loneliness and unprotectedness, utter friendlessness’.

I am very glad I came to Australia, but I cannot say I like it very much, it is such an out-of-the-world place and so monotonous

Others were great observers of the Australian character. According to Gertrude Gooch, ‘All Australians ride like Arabs, love luxury and money. They live very much out of doors and eat great quantities of fruit’. The women ‘are certainly very indolent and untidy’, which explained their offspring: ‘Australian children are just like the vegetation here for neither appear to submit to much control. Pineapples, peaches and the finest fruit grow in open air without care and the children are equally wild and impetuous’.

Great Expectations tells of the colonial experiences of a particular group of emigrant women, but it also tells a broader story, of emigration, education, class prejudice and the development of Australian society.

NLA Publishing

$29.99 Original price was: $29.99.$24.99Current price is: $24.99.

5 in stock

Description

Teach your protégées to emigrate; send them where the men want wives, the mothers want governesses

For educated middle-class women in nineteenth-century Britain, options were limited. Marry and bear children, accept the drudgery of keeping house for relatives or friends, or attempt to find a position in one of the very few industries that would employ women. This is the story of a group of intrepid ladies who found a different solution on the other side of the world.

Wanted, a Governess competent to teach music, dancing, and the usual branches of education. Respectable references required.

The Female Middle Class Emigration Society scheme helped governesses and would-be governesses emigrate to the colonies from 1861 to 1886. The women who participated were encouraged to write back to the society, and it is their letters—sometimes plaintive, sometimes upbeat—that form the heart of this book. Written by women who were often fluent in multiple foreign languages, skilled artists and musicians, able to teach the liberal arts, as well as algebra and geometry, the letters describe wildly different experiences and stories of culture clash abound.

In my new home I shall make acquaintance with a new class of people—the nouveaux riches, but I may consider myself now colonized

Some women gained employment with well-established families even before their ships had docked, formed close relationships with their employers or found husbands. Dublin-born Mary Bayly had a heavy workload teaching the six Hills children of Cooks River, New South Wales, English, French, German, Latin, music and singing, but her employers were ‘very kind’, she found the Australian scenery beautiful—‘As to the Harbour and the views over the sea, they can never to me lose their charming freshness and attractiveness’—and she eventually married an Australian-born teacher who would rise to the position of headmaster, thereby retaining her middle-class status.

Be sensible, undergo a little domestic training and come out here to take your chance

Some women battled extreme loneliness, wild colonial boys and girls, unsupportive employers, poverty and disillusionment. Rosa Phayne, daughter of an accountant, considered her fellow ship passengers ‘so very low and horrid a set’, described Melbourne as ‘beyond anything abominable in every respect’ and, despite finding a position on a sheep station in the Victorian Wimmera, wrote that her employer had ‘not one feeling like a lady, although one ostensibly’ and declared life in Australia for a governess one of ‘intense loneliness and unprotectedness, utter friendlessness’.

I am very glad I came to Australia, but I cannot say I like it very much, it is such an out-of-the-world place and so monotonous

Others were great observers of the Australian character. According to Gertrude Gooch, ‘All Australians ride like Arabs, love luxury and money. They live very much out of doors and eat great quantities of fruit’. The women ‘are certainly very indolent and untidy’, which explained their offspring: ‘Australian children are just like the vegetation here for neither appear to submit to much control. Pineapples, peaches and the finest fruit grow in open air without care and the children are equally wild and impetuous’.

Great Expectations tells of the colonial experiences of a particular group of emigrant women, but it also tells a broader story, of emigration, education, class prejudice and the development of Australian society.

NLA Publishing

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Michelle Staff –

Excerpt of the review by Michelle Staff for the Victoria History Journal, Issue 295, Volume 92, Number 1, June 2021

Colonial Australia was shaped by movement. From the invasion of Aboriginal lands to the various waves of migration that followed, mobility across and within borders was fundamental to the development of the colonies. Living, breathing people were at the heart of this process. Tracing their boundary-crossing lives—including their thoughts, feelings, and experiences—is one way that we can try to understand the past and what it might have been like for at least some of the people who lived through it.

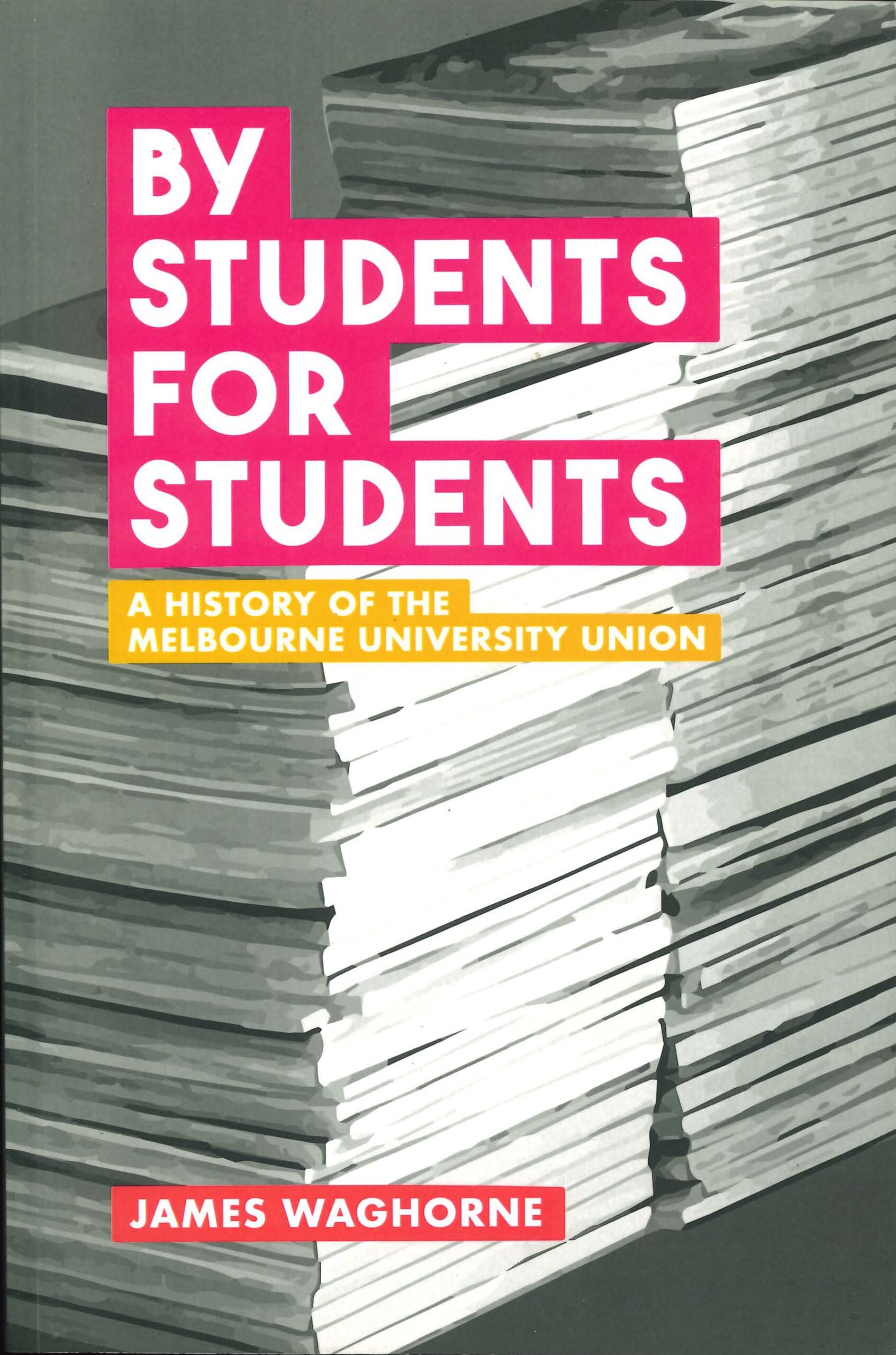

Such is the approach Patricia Clarke takes in her new book, Great Expectations: Emigrant Governesses in Colonial Australia. This work explores the transnational lives of a group of middle-class British women who left unemployment and poor marriage prospects behind to search for work as governesses in the Australian colonies. The journeys of this group—who arrived a few at a time from the early 1860s through to the early 1880s—were financed by loans from the London-based Female Middle Class Emigration Society (FMCES). In this book Clarke revisits the material that formed the basis of her 1985 work, The Governesses: Letters from the Colonies 1862–1882, namely the letters written by the emigrant governesses to the FMCES. Whereas her earlier book focused largely on these women themselves, quoting their letters at great length, in this venture Clarke uses their lives not only to capture their own thoughts and experiences but also to paint a broader picture of the Australian colonies.

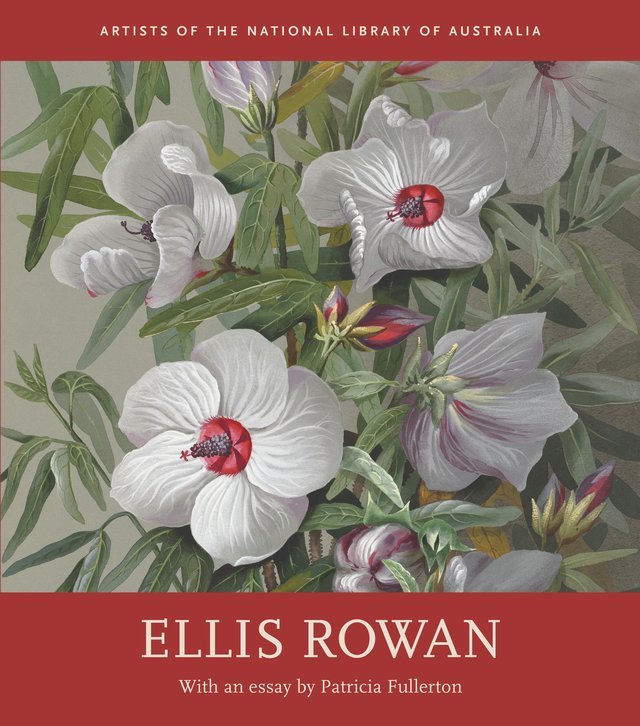

The book itself, published by the National Library of Australia, is beautifully produced. The pages abound with colour copies of historical photographs, portraits, paintings, drawings, advertisements, cartoons, and news clippings. This gives it an exhibition-like quality; Clarke’s highly readable prose and the visual material complement one another and bring the story to life. Though the FMCES governesses numbered only a few hundred, Great Expectations shows that their relative insignificance in the story of migration to the colonies does not lessen the value of their life stories—and their archives—for interrogating the Australian past.