MS 000272 Papers on the Rosstown Junction Railway

By Benjamin Petkov

Dreaming is a commodity. For industrialists, it’s a necessity. Yet an engineer, a carpenter or a surveyor can’t rely on ambition alone to accomplish their visions. With building cities, industries and corporations, building mass enterprises and constructing a cultural fingerprint, the spectator’s vision can easily become obscured. Blinded by glory, success and fortune, emphasis is paid to those that achieved their dreams – and not unduly. However, those that just fell short are either mocked – or given the luxury of having their memory forgotten deep within the archives. The underdog, whose business venture for one reason or another collapsed. The industrialist that couldn’t compete with their contemporaries and eventually had to liquidate. The dreamer whose dreams weren’t backed with the adequate drive, finances or company, to break through all problems, be they accidental or bureaucratic, to eventually actuate them. Within this, underlying their failures, there’s a certain element of romance. The sheer scale of their fall from grace almost demands respect. Nevertheless, without the necessary emphasis or attention, their historical efforts go unknown.

Yet, if you look, the scars of failed industrialists can still be seen in the outer suburbs. Especially if you look from the sky.

If one were to open a Melways Street Directory and look at the roundabout joining Poath Street and Kangaroo Road in Murrumbeena, they’ll notice a curvature stretching from Galbelly Reserve to the Hughesdale Community Centre. This curve continues through the roundabout, and follows the bowed Murrumbeena Crescent. On Google Maps, one notes the houses surrounding the curved roads are all in their grid-allotments. However, the buildings behind the community centre seem awkwardly slotted in –filling a space they almost shouldn’t be.

Simply put, this is because they shouldn’t be there.

If one were to walk from Oakleigh Station, through the lush Galbelly Reserve, past the Hughesdale Community Centre and onwards to Murrumbeena Crescent, they’d be walking the final stretch of Murray Ross’ dead railway – the Rosstown Railway Junction.

The Rosstown Railway Junction was the brainchild of one William Murray Ross – an entrepreneur and industrialist born in 1825. Working as an insurance broker for the Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company, Ross would move to Melbourne in 1852, and secure employment at their Collins Street residence of no. 415-7.

The Rosstown Railway Junction was the brainchild of one William Murray Ross – an entrepreneur and industrialist born in 1825. Working as an insurance broker for the Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company, Ross would move to Melbourne in 1852, and secure employment at their Collins Street residence of no. 415-7.

However, as Jowett and Weickhardt stipulate in Return to Rosstown, it was in 1857 that Ross would begin his newest business venture – the purchasing of land for future subdivision and development. Purchasing 20 acres of land in the middle of Caulfield, he would go on to buy a further 200 acres in 1859, and then a staggering 1000 acres. By the mid-1860s, Murray Ross was the primary holder of more than one-fifth of Caulfield, worth an approximate total of £20,000 – a grand sum in the 1860s. With his land in tow, Ross posted an advertisement in The Argus in 1875, proclaiming “MURRAY ROSS has CONVERTED his ESTATE into a TOWNSHIP”. The township in question was modestly donned Rosstown, and in turn represented Ross’ shift from purchasing land, to developing it. However, this would do him little good if prospective residents couldn’t even get there.

By referencing Isaac Selby’s, “The Old Pioneer’s Memorial History of Melbourne”, of which the RHSV holds a first edition print, one finds a short biography. Glowing with praise, Selby’s short account of Ross’ work with Rosstown is seen to be suitably… romanticised –

“Ross, after whom the original town was named, was a remarkable man. He was brought out by the Liverpool London and Globe Insurance Co. Being frugal and thrifty he accumulated money to buy land in this locality in blocks. He bought constantly over a period of years, until he had an estate seven miles long and one and a half broad, then he built a sugar mill, and tried to get the farmers around to grow sugar. He had a private Railway Bill passed through the Legislative Assembly, and laid down a railway. It is said that about this time he married his second wife. She was much younger than himself, and like most elderly men who secure such a prize, he was proud of the venture, and celebrated the event by opening the railway line. The train ran that day, but it was he first and only train that ever ran on that line. His fortune seemed to be in jeopardy, but the land boom came and he saw the advantage and sold the land. Unfortunately at the stage, his right hand lost its cunning, and he put his money into all kinds of bogus companies – Tasmanian silver mines, brewery companies and other wild cat schemes. He not only lost the money he put in, but in some cases incurred other liabilities. Finally he died in the house of a market gardener in the district in a state of destitution.” Isaac Selby, 1924

“Ross, after whom the original town was named, was a remarkable man. He was brought out by the Liverpool London and Globe Insurance Co. Being frugal and thrifty he accumulated money to buy land in this locality in blocks. He bought constantly over a period of years, until he had an estate seven miles long and one and a half broad, then he built a sugar mill, and tried to get the farmers around to grow sugar. He had a private Railway Bill passed through the Legislative Assembly, and laid down a railway. It is said that about this time he married his second wife. She was much younger than himself, and like most elderly men who secure such a prize, he was proud of the venture, and celebrated the event by opening the railway line. The train ran that day, but it was he first and only train that ever ran on that line. His fortune seemed to be in jeopardy, but the land boom came and he saw the advantage and sold the land. Unfortunately at the stage, his right hand lost its cunning, and he put his money into all kinds of bogus companies – Tasmanian silver mines, brewery companies and other wild cat schemes. He not only lost the money he put in, but in some cases incurred other liabilities. Finally he died in the house of a market gardener in the district in a state of destitution.” Isaac Selby, 1924

Whilst Ross attempted to build his suburb and fight off encroaching mortgagors, he was simultaneously laying the foundations for a separate business venture, and one that would blight Caulfield’s landscape for decades after its construction. In this, the mantra – a war is never won when fought on two fronts – rings in the distance. Ross, between what is now Truganini Road and Munro Avenue, running perpendicular to Koornang Road, built a monolithic sugar mill – designed to extract sugar from beetroots. Seeking to emulate the success of Duncan of Lavenham some years prior, who had found sugar-beet production particularly lucrative, the construction of the sugar mill in 1875 is remarked to have spelled the beginning of Murray Ross’ end.

By constructing the sugar mill – Ross simultaneously bought the surrounding public land, which concurrently restricted the local market gardener’s access to both water and peat. The public outcry was immense, and Ross inadvertently embittered the very people his burgeoning new business relied on. Ross depended on the local market gardeners to grow and produce the sugar beets necessary for his mill to function, and with their stalwart refusal to do just that, Ross’ venture looked as if it were to fail before it had even fully begun.

It was in this atmosphere of adversity and beetroots, that Ross was forced to redesign his production plan. Rather, instead of producing the required beetroots locally, they would be bought and transported from Gippsland. Herein, Ross was met with one major issue: how was he going to transport tonnes and tonnes of beetroots all the way from Gippsland to his sugar mill in the heart of Caulfield? The Rosstown Railway Junction.

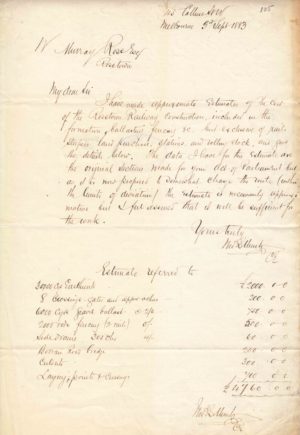

Initially designed to be a single line running from Elsternwick to the Rosstown Sugar Mill, Ross’ petition was denied in 1875 by the Legislative Assembly. Taking their refusal on board, Ross in 1876 resumed his petition, with the legal help of Malleson, English and Stewart. Recognising the need for public access to his new development as well as the need to transport beetroots to his mill, whilst also needing to appeal to both the legislative assembly and Victoria Rail – Ross extended his prospective line. Instead of being a single line running from Elsternwick to the sugar mill, the line would continue onwards to in turn join the Gippsland line. Evidence of the petitioned line can be seen in the plans held by the RHSV, including all independent plans for stations as well as the plan offered to the Legislative Assembly in 1884. However, dealing with both Victoria Rail’s mistrust of privately owned railways, and the Gippsland Line’s outrageously high tariffs – Ross thought it better to finish his line at Oakleigh Station. The ensuing line would be a junction joining Elsternwick with Oakleigh Station. By referring to Ross’ plans, held by the RHSV, one can recognise the sheer scale of the exploit. Similarly, they’d notice how lucrative the proposal would be, if successfully petitioned and constructed. Not only would Ross’ Sugar Mill receive the necessary beetroots for sugar-production, but the value of his landholdings would almost double.

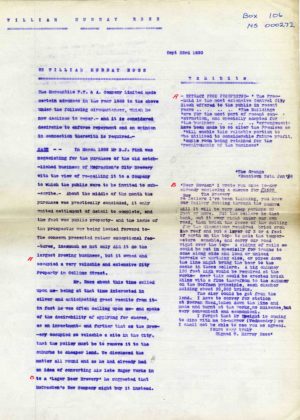

Construction of the Rosstown Railway Junction from Elsternwick to Oakleigh was officially authorised on the 14th of November 1878, through the legislative passing of Act 614. Given 5 years to build the line, Ross rapidly fell behind. Juggling the land development, the mill, the line as well as all ensuing debtors, Ross sought an extension on his 5 years, which was in turn granted. Financially flagging, Ross was forced to mortgage over half of his holdings – including his primary residence, “The Grange”. Seeking to fund his projects with funds procured through loans and bank payouts, one can see Ross was flailing. With the help of the Mercantile Financial Company (MFC) however (pictured below), of which one Thomas Bent, the budding State Premier, was a major shareholder, Ross was able to secure the funds necessary to complete construction. Yet, through all this, the line was officially opened in 1888, though it technically hadn’t yet been completed. The work was shoddy and expenses had been saved using worn materials. It’s recorded that the sleepers were second-hand, as were the rails – some of which were bowed and, allegedly, only secured every fourth sleeper.

However, by September 1887, Ross needed to sell. Racked with debt and financially unable to continue alone, he, with Bent and other shareholders decided to sell the company – to themselves. Selling the junction, complete with Ross’ budding suburb and failing sugar mill, to the newly formed “Rosstown Junction and Property Company” (RJPC), Ross was able to stir social ‘hype’.

A fire-sale ensued and Ross was able to recoup a minor amount of funds from the menial sales. Ross’ independent business was sold to the new company for £50,000 – in the form of 10,000 £5 shares. Pictured below, one notes the RHSV holds a sizeable amount of these shares, and whilst their investment value has seemingly long since dwindled, their historical value is of utmost importance when recognising Ross’ attempts to recoup his expenses by appealing to investors.

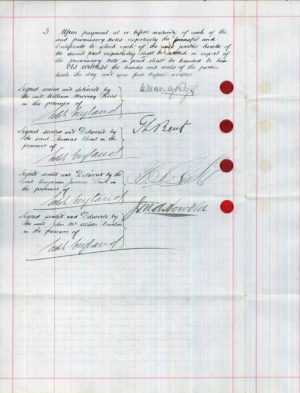

Alongside the shares, one notes the “Memorandum of Association and Articles of Association of the Rosstown Railway Junction and Property Co. Ltd.”, which works to list the companies’ statutes – but of even greater importance are the deeds of ownership to the company, complete with all major shareholder’s signatures.

It was also in this period when Ross entered into ‘confidential’ negotiations with one Soon Hang Hi (this is expected to be misspelt), of “Le Rue de Petit-Bourke”. Hi’s name is only mentioned once within the Ross collection, on a single document. Though a translation hasn’t been achievable, (click here for more information), one’s interest is sparked –

“Confidential…That portion of the document referring to taxes you will notice I have underlined so that your attention may be drawn to it; but I think that upon your perusal you will agree with me that my bargain is highly satisfactory to the Company. Mr. John Grieves Fraser will explain any idiomatic phrases in the agreement which may, in the instant, puzzle you. Yours faithfully – R. Lundon”

It was on the turn of the century however, when Ross was forced once again to reevaluate his plans. Debts accruing from funds borrowed from the MFC in 1888 had reappeared in the form of a long and protracted legal case in the Supreme Court. By addressing the minutes held by the RHSV, one notes Ross’ guilt was expected. Ross, it appeared, had used funds procured through MFC loans in 1888, to purchase shares in silver. When said shares would collapse, he was left with no return. He similarly bought a brewery, hoping to profit from yet another separate enterprise. His answer to the grounds for repayment were stated simply: “I didn’t think I needed to pay them back”.

The pressures of Ross’ burgeoning debts were only exacerbated by Victoria Rail. Victoria Rail, in 1897, threatened and in turn executed the complete deconstruction of all Rosstown Railway junctions, trackwork and signals. Though all equipment would ultimately be restored to Ross, under further legal duress, the damage to the already shoddy line was irreparable. Though Ross continued in 1900 to lobby the government to purchase the line from the RJPC, his overinflated valuations held back any transaction. At the time, Ross disseminated a rumour that upon his second engagement, a single train ran on the Rosstown line, carrying himself, his fiancé and Thomas Bent. This was never verified, and it seems improbable as the line was never fully connected. The line was in disarray, as was the forgotten Sugar Mill, and there was no way to repay debts.

William Murray Ross, disgraced and divorced, died in his sleep in September 1904, at the age of 79.

Further Reading

D.F. Jowett and I.G. Weickhardt’s Return to Rosstown

Glen Eira City Council : Rosstown Rail Trail

Royal Historical Society of Victoria : Papers of the Rosstown Junction Railway

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm