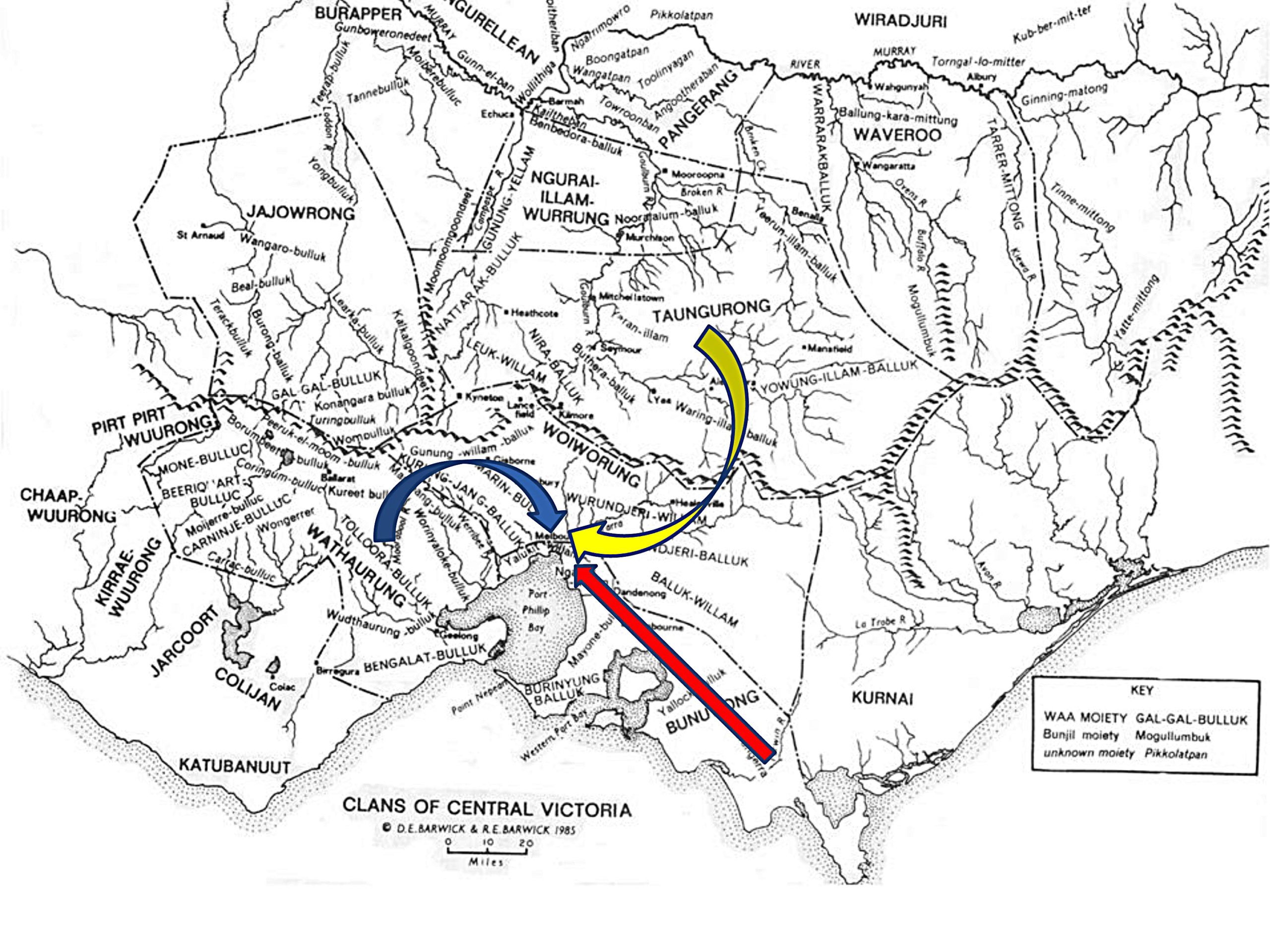

‘’Clans of Central Victoria’ by D E and R E Barwick, 1985, Mapping the Past: an atlas of Victorian Clans, 1835-1904, by Dianne Barwick in Aboriginal History, Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (1984), p. 118. Kulin movements annotated by Gary Presland, 2020

‘By what I can learn, long ere the settlement was formed the spot where Melbourne now stands and the spot on which we are now camped [on the south side of the Yarra, near the Botanic Gardens site] was the regular rendezvous for the tribes known as Waworangs, Boonurongs, Barrabools, Nilunguons, Gouldburns twice a year or as often as circumstances and emergencies required to settle their grievances, revenge deaths, etc.’ William Thomas, Assistant Protector of Aborigines, 1840

Before European settlement, West Melbourne Swamp played an important rôle in the Kulin world. Once or twice a year people from all of the language groups that made up the Kulin nation would gather in the area around the lower Yarra River. Hundreds of people would camp in traditional sites around the river and over a period of three or four weeks take part in meetings, ceremonies, and social gatherings. Gatherings of such numbers were possible only because of the many wetlands close to the lower reaches of the river. These waterscape features were the most productive areas in the region. People from the clans of Watha Wurrung speakers came from the Bellarine Peninsula and camped on the rising ground adjacent to West Melbourne Swamp. Boon Wurrung speakers traditionally camped on the ridge along the south side of the river, in the area that now includes the Botanic Gardens. From there they had easy access to a large freshwater billabong. People from Taung Wurrung country, in the Goulburn and Ovens River valleys, set up their camps adjacent to the Yarra in the Collingwood area, where there were wetlands. The local clans, of the Woi Wurrung language group, made use of the many wetlands that flanked the river on its northern side, upstream of Princes Bridge.

A group of Indigenous people looking west along Collins Street, 1840 RHSV Collection BL84-005

Before Europeans arrived in the Port Phillip district, the large wetland that lay between the Yarra River and the Moonee Ponds Creek sustained the life and cultural traditions of the Kulin nation, the First Nations people who occupied the area of central Victoria from the Murray River to Bass Strait. The Kulin nation comprised the eastern Kulin (Woi wurrung, Boon wurrung, Taung wurrung and Ngarai illam-wurrung), and the western Kulin (Watha wurrung, and Dja Dja warrung). The Europeans first called the wetland Batman’s Swamp, and later the West Melbourne Swamp. Unless it was a dry year, the wetland was teeming with life, and able to sustain large gatherings of Indigenous people to enable them to conduct important ceremonial business. This included arranging marriages, initiations, trade, settling disputes, permission to cross boundaries or hunt in neighbouring estates, and collecting material for future activities. As part of these gatherings, ceremonies were performed for the clans to display their talents at dancing, singing, and personal ornamentation.

Albert Mattingley, who arrived in Port Phillip in 1852, recalled in 1916 that “on the waters of a large marsh or swamp graceful swans, pelicans, geese, black, brown and grey ducks, teal, cormorants, water hen, seagulls… disported themselves, while curlews, spur-winged plover, cranes, snipe, sandpipers and dotterals either waded in the shallows or ran along its margin, and quail and stone plover…were very plentiful…Eels, trout, a small species of perch about 2 inches long, and almost innumerable green frogs inhabited its waters”.

In addition to the birds, eels and fish, the area supplied tubers, medicinal plants, and reeds for basket making. The wetland resources supported the social and ceremonial aspects of the Kulin world. The saltwater lagoon noted by early explorers had two main sources of water – the Moonee Ponds, Creek, and other small rivulets entering from the direction of Royal Park; and flooding from the Yarra River. It had no direct outlet to the ocean.

As early as 1837 surveyor Robert Russell noted that at times the lagoon was quite dry. The lagoon was wide and shallow and surrounded by a large area of brackish marshland.

It was no co-incidence that both Kulin people and the Europeans chose the same location to camp at the place that became Melbourne. Freshwater was the attraction to both groups. However, Europeans and their livestock could only cause injury to the food and water sources that sustained the Kulin people. Soon, not only food but particular locations became difficult for Kulin people to access.

“Aboriginal land use practices also had impact on the local habitat. Their use of fire-stick farming, for instance, had created the open grasslands that were so attractive to the European pastoralists who were first to arrive. Most likely over thousands of years, flora and fauna had also been impacted. Aboriginal land use as it was practised in south-eastern Australia was of a character too subtle for the great majority of imperceptive white observers to notice the impact it was having on the land.” G Presland, The Place for a Village: how nature has shaped the city of Melbourne, p 14.

The Kulin people had established complex cultural and traditional movements about their estate which were intimately understood by each culture group. These movements took advantage of the abundance of certain flora and fauna at different seasons and took into account the places which gave shelter during the coldest or wettest times of the year. From 1835 each time their path took them back to Melbourne they would find the European invaders had continued to impact on the area until they were no longer able to sustain their traditional life

The European sheep farmers arrived with different cultural attitudes to land ownership and management. Swamps were considered a source of disease and regarded as a wasteland. The settlers were essentially pastoralists and merchants, in whose interests flood mitigation and port facilities needed to be developed. Talk of ‘reclamation’ began in the 1840s.

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm