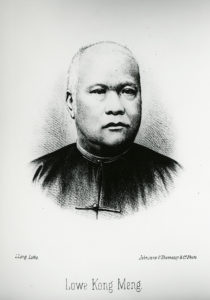

This sketch from over 100 years ago features a man who may not be known by all Australians, but played an important role in the history of the Chinese-Australian community. Amongst the backdrop of uncertainty and discrimination faced by Chinese immigrants during the 19th century, he would become one of the most successful and respected Chinese-Australians of the era.

This sketch from over 100 years ago features a man who may not be known by all Australians, but played an important role in the history of the Chinese-Australian community. Amongst the backdrop of uncertainty and discrimination faced by Chinese immigrants during the 19th century, he would become one of the most successful and respected Chinese-Australians of the era.

Lowe Kong Meng was born a British subject in Penang, Malaysia in 1831[1], and it is believed that his ancestors may have originated from the Sam Yup (Three Counties) region of China, near Canton[2]. As Paul Macgregor elaborates, Penang was a British colony at the time, not only growing as a trade port, but had introduced colonial ways of life such as newspapers and one of the first English schools in South-East Asia[3]. At 16, Kong Meng was educated in French and English by private tutors in the then-British colony of Mauritius[4]. This education and upbringing would influence his future path in life as it equipped him with the language skills needed to adapt to the customers and clients he would later make business with.

With his father already part of a century-old merchant and contractor business[5], it was not long before Kong Meng would follow his father’s footsteps. After his education, Kong Meng spent the next few years trading with merchants at Mauritius, Calcutta and Singapore as a supercargo (a role that required the management of a ship’s cargo during a trip)[6]. Around this time, gold had been discovered in Australia, luring the young man to sail to Victoria on his own ship in 1853[7]. He spent three months at the diggings, before he left Australia feeling he was wasting his efforts on “unprofitable adventure”[8]. It was only through the encouragement of his friends that he was convinced to come back[9].

Fortunately, his return to Victoria in 1854 proved to be much more successful. He set up a business at Little Bourke Street known as Kong Meng & Co[10]. One of the earliest mentions of his first business is an 1855 article from The Argus on a missing drayman (who was delivering goods for Kong Meng), which records the address being at 65 Little Bourke St East[11] (or what is now 208 Little Bourke St). The shop was later moved to 102 Little Bourke St East[12] (now 171 Little Bourke St), before it settled at 94 Little Bourke St East (now 183 Little Bourke St) in the 1860’s[13]. At the time, Little Bourke Street was just opening its first lodging houses for Chinese immigrants, with miners using the area as a place to pick up supplies before heading to the goldfields[14]. It is likely Kong Meng’s business was one of many in that street that capitalised on this, especially as his business sold imported goods such as tea, rice and sugar[15], and Macgregor notes that he often sold his stock wholesale[16]. Considering the aforementioned Argus article, where the missing supplies were being sent to Bendigo, it’s possible this wholesale method was used for deliveries into the goldfields, where many Chinese (and non-Chinese) had settled.

However, this shop was only the tip of the iceberg. On top of his expertise as a merchant, Kong Meng also owned as many as six ships that constantly sailed the seas near China, India and Australia on business[17]. The Argus would later give him the moniker “the first Chinese shipmaster in all the colonies”[18]. Kong Meng’s cargo was recorded to be worth as much as £10,000, which would be worth millions today[19]. His ships would later procure the delicacy beche-de-mer (sea cucumbers) from the Torres Strait, and he was amongst the first to try trading from Port Darwin to Victoria[20] (though his obituary in The Argus states that he was unsuccessful)[21]. He was reportedly one of the wealthiest men in Victoria as Kong Meng and Co. had “establishments in Hong Kong, in the Mauritius and in London”[22]. He also capitalised on the mining industry, financing several mining ventures, and owning a mine at Majorca, Victoria, known as Woah Hawp[23].

What makes his success startling for some was that it happened during a time when relations between Chinese and Australians experienced some testing times. From 1854 there was a massive spike in the Chinese immigration as a response to the gold rush, with over 18,000 Chinese immigrants arriving in an 18-month period[24]. By 1859, around 46,000 were living in Victoria[25]. Many of these arrived by themselves, intending to send any fortune they earned back to their families at home[26]. Others were paying back debts they owed for passage to Australia in the first place[27]. However, the presence of Chinese and the rate they were entering the colony were enough to alarm sections of the population. Some miners saw these new visitors as further competition for gold[28]. For others, their concerns were more racially charged, seeing the Chinese as a threat to Colonial life. For example, an 1855 Commission on the Goldfields accused the Chinese of “demoralising colonial society” through their living habits, reputation for gambling, and religion[29]. Elsewhere, an Argus article on a Chamber of Commerce meeting considered the public’s fears that Chinese immigration would “entirely swamp the present population”[30].

It should be noted that such views did not reflect the whole population. A notable exception to this rhetoric was surgeon George Henry Gibson, who gave evidence in the 1855 Commission on the conditions on the goldfields, stating that he had no ill feelings toward them and that they were a “most quiet, inoffensive class of persons”[31]. However, paranoia about a perceived invasion of Chinese heightened anti-Chinese sentiments amongst many colonists. William Kelly reported that Chinese in Ballarat were “regarded with undisguised enmity by the European diggers, and subjected to every species of injustice and cruelty”[32]. Sometimes confrontations with the Chinese became violent, such as the riots at Buckland Valley in 1857, where thousands of Chinese were chased off their camps, had their tents burned, and three drowned trying to flee[33].

In response to public concerns and hostility, the Victorian government introduced several laws that were designed to reduce the flow of Chinese immigration. The 1855 Chinese Immigration Act placed a limit on how many immigrants could enter, based on one person per 10 tons of cargo[34]. Later amendments added a £10 landing fee[35], and a £6 yearly protection fee[36] (later reduced to a £4 residence tax[37]). Many Chinese would avoid this just by landing at other colonies and arriving to Victoria by foot[38]. But until these laws were temporarily abolished in 1863[39], thousands of Chinese who refused to pay would be fined or imprisoned[40]. Even Kong Meng himself was not immune to these restrictions. An 1859 Argus article reports him on trial for refusing to pay the tax, with the merchant claiming he should be exempt as he was born on British territory[41]. However, he was forced to pay due to a lack of “collateral evidence” of his parent’s status as British subjects[42]. Kong Meng was also a victim of some uncomfortable situations due to his heritage. John Butler Cooper’s History of Malvern identifies an incident when Kong Meng was on a horse-drawn bus to Prahran, when a fellow traveller started a patronising conversation with him in pigeon English[43]. However, Kong Meng was able to embarrass the man, replying, “Sir, I do not understand your broken English, perhaps it happens that you speak French somewhat better or…maybe perhaps you speak Chinese?”[44]

Despite the issues going on with his fellow Chinese however, Kong Meng was largely respected by the Colonial community. Amongst the RHSV archives is a photocopy of an address from 1863. At the time, Kong Meng was moving from his home at Park House, Moray Street, Emerald Hill (now South Melbourne)[45], which would later be the home of premier Sir James Patterson[46], and is now on the Victorian Heritage Register[47]. The address, bidding his farewell from the region, tells us a lot about Kong Meng’s reputation amongst his peers, as it reads like a fond farewell. In particular, it praises Kong Meng for his “zealous support which you have always given to our noble institutions” and hopes “that you may long be spared to exhibit that kind and Christian spirit which has won for you the sympathy and respect of all the inhabitants of this municipality.” The people in the address are not just simple residents either: John Nimmo was a notable surveyor who later served on the Legislative Assembly[48], and Edwin Exon was Superintendent of the Melbourne Orphan Asylum for nearly 50 years[49]. The name on the bottom is from a William McCutchon (possibly an alternate spelling of McCutheon), the president of the Emerald Hill Benevolent Society, an organisation dedicated to helping destitute families in the region[50]. This organisation was later run by women as the South Melbourne Ladies Benevolent Society[51].

(Image: Copy of an address of appreciation from Emerald Hill residents, to Lowe Kong Meng, 1863. MS 001191, Box 261-9.)

(Image: Kong Meng’s former home, Park House, South Melbourne. Source: Author.)

The reasons why a Chinese/Malayan merchant would receive such blessing despite the treatment of his fellow Chinese can be speculated. Geoff Oddie suggests that Long Meng’s reputation as a wealthy businessman may have helped. Geoff mentions that Chinese merchants in the 19th century were not only major contributors to the economy, but were seen as more acceptable to white Australians compared to the lower class migrants[52]. This especially applied to merchants that were prepared to assimilate into colonial society[53]. This is not to say all lower or upper class Chinese were treated in the same way, but Kong Meng did have qualities that helped him into high society. On top of his education, wealth, business knowledge and fluency in English, he was proud of his status as a British subject, especially encouraging his fellow Chinese to respect the British flag, law and justice[54]. The names of several church figures in the address indicate strong ties with the Christian faith, especially as he was well known for giving generously to charities and churches[55]. It is just as likely in Kong Meng’s case that the community were willing to overlook his Chinese ancestry and judge him on the merit of his good character and his service to the community. This goodwill may have extended to his marriage to Tasmanian-born Mary Ann Prussia (Circa 1842-1913), with whom he had 12 children[56].Whilst authors such as Kate Bagnall note that some mixed-race relationships in this period were at times met with discrimination[57], any disapproval the couple may have had did not appear to be public. For example, when both attended a fancy dress ball that honoured the 1867 visit of the Duke of Edinburgh (Prince Alfred), The Argus does not appear to raise a fuss about their marriage, being more interested in reporting Kong Meng’s outfit[58].

Even with his status as a British citizen, Kong Meng remained supportive of the Chinese. When interviewed over Chinese immigration in 1856, Kong Meng stated his own concerns on the restrictive laws stating “A good many (immigrants) say, if they settle here this year a tax may be put on them next year. They are frightened. They do not know the law.”[59] Later, around the time of his 1859 trial about his non-payment of the Chinese residence tax, Kong Meng took the fight beyond his own personal grievances. He not only put up a petition against the residence tax[60], but with a delegation of Chinese merchants had a meeting with Victorian Chief Secretary, John O’Shannassey[61]. There they pleaded to be exempt from the entry tax due to their constant travelling[62]. Whilst Macgregor notes the merchants were protesting for the benefit of the merchant class rather than for all Chinese (such as the working class)[63], it at least shows that Kong Meng was able to bring the fight to the wider issue of discrimination.

Kong Meng would continue to fight against discrimination throughout his life. In 1878, a seaman’s strike was ignited when the Australasian Steam Navigation Company used Chinese sailors for trips between Fiji and New Caledonia at half the cost[64]. The strike soon gained support by anti-Chinese organisations[65]. In response, Kong Meng, missionary Cheong Cheok Hong (Circa 1853-1928) and fellow businessman Louis Ah Mouy (1826-1918) would co-write a pamphlet titled The Chinese Question In Australia in 1879. The pamphlet argued against the anti-Chinese sentiments in the nation, stating that Chinese citizens should have the right to enter a colony of England under the treaties China and England had previously made[66]. Their argument also highlighted the benefits of Chinese Immigration to Australia’s development at the time, such as their contribution to the improvement of health through vegetable cultivation[67].

Kong Meng’s support for the Chinese became significant in the 1880’s, as further anti-Chinese sentiments and concerns about competition for employment grew[68]. This would see the return of anti-Chinese legislation, which heavily restricted the naturalisation and immigration of Chinese[69]. Amongst this backdrop, in 1887, Kong Meng helped produce a petition that protested against those demands, which was given to the visiting Chinese commissioners General Wong Yung Ho and U Tsing[70]. By 1888, when Anti-Chinese sentiments prevented several ships (notably the SS Afghan and SS Burrumbeet) from letting Chinese immigrants land, Kong Meng was amongst those who helped in the negotiations for their release[71].

Kong Meng also helped the Chinese community in other ways. In the 1860’s, he helped fund the construction of the Num Pon Soon Society building, an organisation for people of the Sam Yup district[72]. The Society was one of several district-of-origin associations that helped provide mutual support and orientation of Chinese immigrants[73]. He was able to find employment for Chinese immigrants, whether it was in his mines[74], or working on garden plots on his Malvern property[75]. He also gained a reputation for settling disputes between his people[76], and assisted in setting up a relief fund for the China famine in 1878[77]. He was so renowned as a leader of the community that the then-Emperor bestowed him the title of the Mandarin of the Blue Button, civil order, in 1863[78].

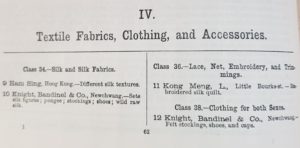

In his eventful life, he also had a hand in several other businesses and events, whether in Melbourne or Australia-wide. He was part of the provisional committee for the Commercial Bank of Australia (one of the banks that became Westpac)[79]. He also represented several insurance companies (On Tai and Man On), and is also credited as a founder of the Hop Wah Sugar Company in Cairns in 1882[80]. He was even a member of the scientific organisation, the Royal Society of Victoria[81]. Outside of business, he was also involved with social events that affected Melbourne, being elected to the role as commissioner of the Melbourne Exhibitions of 1880 and 1888[82]. His role in the 1880 event notably saw him donate an embroidered silk quilt for use in the Chinese court of the Exhibition[83].

(Picture: 1880 Intercolonial Exhibition catalogue extracts. Picture source: author)

When he died in October 22nd 1888 at his Malvern home due to “congestion of the kidneys”[84], it was reported that if he’d lived longer, he could have been appointed “the Chinese Consul-General for Australasia”[85]. How respected he was by Victorians was evident when he was taken to the Melbourne Cemetery, with about 100 vehicles escorting his body, and many Chinese and non-Chinese people witnessing his farewell[86].

After his death, the Kong Meng family would continue to be in the news. In World War One, his son George (1877-1953?) gained sympathy from the populace when he was rejected from army service for his non-European ancestry[87]. George’s angry reply reflects his frustrations in a post-federation White Australia, stating “England and France deem it fit to use coloured troops to defend their shores, but the great Australian democracy denies its own subjects the same opportunities”[88]. Curiously, his brother Herbert (1866?-1955) was already serving his country at the same time, and was promoted to sergeant before being discharged due to ill health[89].

Today, Lowe Kong Meng should be remembered as a figure who lived an amazing life. During a period known for its anti-Chinese discrimination, he still achieved much. He was a successful merchant and businessman, and proud British subject who successfully mingled with high Colonial society despite his Chinese heritage. He was also a respected leader amongst the Chinese, who actively campaigned against anti-Chinese attitudes and legislation. The Emerald Hill Address adds one more accolade to his story: a beloved friend who no one wanted to leave so soon.

References:

[1] Yong, Ching Fatt, ‘Lowe Meng Kong (1831-1888)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 5, (MUP), 1974, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lowe-kong-meng-4043.

[2] Macgregor, Paul, ‘Chinese Political Values in Colonial Victoria: Lowe Kong Meng and the legacy of the July 1880 Election’, Couchman, Sophie, Bagnall, Kate (eds), Chinese Australians, Politics, Engagement, and Resistance, Brill, Koninklijke Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015, p. 69

[3] Macgregor, Paul, ‘Lowe Kong Meng and Chinese Engagement in the International trade of Colonial Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, No.11, 2012, https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2012/lowe-kong-meng-and-chinese-engagement.

[4] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[5] Macgregor, 2012.

[6] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Herald, “The Chinese In Victoria: Kong Meng”, 17th August 1863, p. 4.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[11] The Argus, June 14th 1855, p. 8.

[12] The Argus, February 26th 1859, p. 1.

[13] Sand and McDougall’s Melbourne and Suburban Directory for 1868, Sands and McDougall, Collins St West, 1868, p. 10.

[14] Couchman, Sophie, ‘Melbourne’s Chinatown- Little Bourke Street Area’, Chinese-Australian Historical Images in Australia, http://www.chia.chinesemuseum.com.au/biogs/CH00015b.htm.

[15] Report of the select committee of the legislative council on the subject of Chinese Immigration together with the proceedings of the committee and minutes of evidence, 1857, p. 11.

[16] Macgregor, 2012.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The Argus, ‘The Late Mr. Kong Meng’, 24th October 1888, p. 16.

[19] King, ‘Chinese Residence Tax’, The Argus, 31/5/1859, p. 7, cited in Macgregor, 2012.

[20] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[21] The Argus, ‘The Late Mr. Lowe Kong Meng’.

[22] Ibid., “Our Oriental Traders”, 14th April 1863, p. 5.

[23] Cronin, Kathryn, Colonial Casualties: Chinese in Early Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1982 p. 28.

[24] Price, Charles A., The Great White Walls Are Built: restrictive immigration to North America and Australasia 1836-1888, Australian National University Press, Canberra 1974, p.68.

[25] Macgregor, 2015, p. 65.

[26] Cronin, p. 19.

[27] Bowen, Auster, ‘The Merchants: Chinese Social Organisation in Colonial Australia’, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 42, No.1, 2011, p. 31.

[28] Cronin, p. 42.

[29] McLaren, Ian. F., ‘Commission appointed to enquire into the conditions of the gold fields of Victoria 1855. Report, pp.l-liii’, The Chinese in Victoria: Official Reports and Documents, Red Rooster Press, 1985, p. 7.

[30] ‘Chinese Immigration’, The Argus, 26th April 1855, p. 4.

[31] McLaren, p. 7.

[32] Kelly, William, Life in Victoria or Victoria in 1853, and Victoria in 1858, Vol. II, Lowden Publishing Co., Kilmore, Australia, 1977, p.276.

[33] Cronin, p. 55.

[34] Museum of Australian Democracy, ‘Chinese Immigration Act 1855’, p. 1, https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/vic4_doc_1855.pdf

[35] Cronin, p. 95.

[36] Ibid., p. 96.

[37] Ibid., p. 98.

[38] Price, p. 71.

[39] Cronin, p. 101.

[40] Price, p. 73.

[41] The Argus, ‘Police; City Court Thursday June 2nd’, June 3rd 1859, p. 5.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Cooper, John Butler, The History of Malvern 1835-1935, The Speciality Press Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, 1935, p. 126.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Sands and Macdougall, Melbourne and Suburban Directory for 1863, Sands and McDougall, Collins Street West, Melbourne, 1863, p. 171.

[46] South Melbourne’s Heritage: An illustrated guide to the history and development of the city of South Melbourne, City of South Melbourne, Ministry for Planning and Environment, December 1988, p. 40.

[47] Heritage Council Victoria, ‘Park House’, https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/1060

[48] Mitchell, Ann A., ‘Nimmo, John (1819-1904), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, 1974, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nimmo-john-4305.

[49] The Leader, ‘Mr. Edwin Exon’, 4th June 1910, p. 22.

[50] Priestley, Susan, South Melbourne: A History, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1995, p. 69.

[51] Ibid., p. 224.

[52] Oddie, Geoff A., ‘The Lower Class Chinese and the Merchant Elite in Victoria’, Historical Studies, Volume 61, No. 37, November 1961, p. 69.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[55] The Argus, ‘The Late Mr. Kong Meng’.

[56] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[57] Bagnall, Kate, Golden shadows on a white land: An exploration of the lives of white women who partnered Chinese men and their children in southern Australia 1855-1915, PHD thesis, Department of History, University of Sydney, 2007, p.137.

[58] ‘The Duke of Edinburgh in Victoria: The Corporation Fancy Dress Ball’, The Argus, 24th December 1867, p. 6.

[59] ‘Select evidence to select committee on Chinese Immigration’, V&P (Vic., L.C.), 1856-57, Vol.2, p.11.

[60] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[61] ‘Chinese Residence Tax’, The Argus, 31st May 1859, p. 7.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Macgregor, 2012.

[64] Macgregor, 2015, p. 83.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Kong Meng, Lowe, Cheong, Cheok Hong, Ah Mouy, Louis, The Chinese Question in Australia, 1879, p. 4.

[67] Ibid., p.8.

[68] Oddie, p. 69.

[69] Bagnall, Kate, ‘Chinese Australian families and the legacies of colonial naturalisation’, The Tiger’s Mouth, 8th July 2018, http://chineseaustralia.org/tag/immigration-restriction-act/.

[70] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[71] The Age, “The Chinese Question: Movement for Release from Quarantine”, 16th May 1888, p. 5.

[72] Macgregor, 2015, p. 69.

[73] Ibid., p. 73.

[74] Oddie, Geoff A., Chinese in Victoria 1870-1890, University of Melbourne, 1959, p. 22.

[75] Cooper, John Butler, p. 125.

[76] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[77] The Argus, ‘The Famine In China’, 21st May 1878, p. 6.

[78] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[81] Macgregor, 2015, p. 63.

[82] Yong, Ching Fatt.

[83] Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition 1880. Opened 1st October 1880: The Official Catalogue Of the Exhibits, with Introductory Notices of the Countries Exhibiting, Vol. 2, 1880, p. 62.

[84] The Argus, ‘The Late Mr. Kong Meng’, p. 16.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Ibid.

[87] Australian War memorial, “George Kong Meng”, https://www.awm.gov.au/learn/schools/resources/anzac-diversity/george-meng.

[88] ‘Recruiting Stupidity: To The Editor Of The Argus’, The Argus, 24th January 1916, p. 11.

[89] Alice Pung, “Chinese Fortune exhibition charts untold tale of wealth and prejudice”, Sydney Morning Herald, 19/1/2017, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/chinese-fortunes-exhibition-charts-untold-tale-of-wealth-and-prejudice-20170119-gtugzg.html.

Bibliography

Alice Pung, “Chinese Fortune exhibition charts untold tale of wealth and prejudice”, Sydney Morning Herald, 19/1/2017, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/chinese-fortunes-exhibition-charts-untold-tale-of-wealth-and-prejudice-20170119-gtugzg.html.

Australian War Memorial, “George Kong Meng”, https://www.awm.gov.au/learn/schools/resources/anzac-diversity/george-meng.

Bagnall, Kate, ‘Chinese Australian families and the legacies of colonial naturalisation’, The Tiger’s Mouth, 8th July 2018, http://chineseaustralia.org/tag/immigration-restriction-act/.

Bagnall, Kate, Golden shadows on a white land: An exploration of the lives of white women who partnered Chinese men and their children in southern Australia 1855-1915, PHD thesis, Department of History, University of Sydney, 2007.

Bowen, Auster, ‘The Merchants: Chinese Social Organisation in Colonial Australia’, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 42, No.1, 2011, p. 25-44.

Cooper, John Butler, The History of Malvern 1835-1935, The Speciality Press Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, 1935.

Couchman, Sophie, Chinese-Australian Historical Images in Australia, ‘Melbourne’s Chinatown- Little Bourke Street Area’, http://www.chia.chinesemuseum.com.au/biogs/CH00015b.htm.

Cronin, Kathryn, Colonial Casualties: Chinese in Early Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1982.

Heritage Council Victoria, ‘Park House’, https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/1060.

Kelly, William, Life in Victoria or Victoria in 1853, and Victoria in 1858, Vol. II, Lowden Publishing Co., Kilmore, Australia, 1977.

Kong Meng, Lowe, Cheong, Cheok Hong, Ah Mouy, Louis, The Chinese Question in Australia, 1879.

Macgregor, Paul, ‘Chinese Political Values in Colonial Victoria: Lowe Kong Meng and the legacy of the July 1880 Election’, Couchman, Sophie, Bagnall, Kate (eds), Chinese Australians, Politics, Engagement, and Resistance, Brill, Koninklijke Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015, p. 53-97.

Macgregor, Paul, ‘Lowe Kong Meng and Chinese Engagement in the International trade of Colonial Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, No.11, 2012, https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2012/lowe-kong-meng-and-chinese-engagement.

McLaren, Ian F., The Chinese in Victoria: Official Reports and Documents, Red Rooster Press, 1985.

Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition 1880. Opened 1st October 1880: The Official Catalogue Of the Exhibits, with Introductory Notices of the Countries Exhibiting, Vol. 2, 1880.

Mitchell, Ann A., ‘Nimmo, John (1819-1904), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, 1974, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nimmo-john-4305.

Museum of Australian Democracy, ‘An Act to make provision for certain immigrants’, https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/vic4_doc_1855.pdf.

Oddie, Geoff A., Chinese in Victoria 1870-1890, University of Melbourne, 1959.

Oddie, Geoff A., ‘The Lower Class Chinese and the Merchant Elite in Victoria’, Historical Studies, Volume 61, No. 37, November 1961, p. 65-70.

Price, Charles A., The Great White Walls Are Built: restrictive immigration to North America and Australasia 1836-1888, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1974.

Priestley, Susan, South Melbourne: A History, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1995.

Report of the select committee of the legislative council on the subject of Chinese Immigration together with the proceedings of the committee and minutes of evidence, 1857.

Sands and Macdougall, Melbourne and Suburban Directory for 1863, Sands and McDougall, Collins Street West, Melbourne, 1863.

Sand and McDougall’s Melbourne and Suburban Directory for 1868, Sands and McDougall, Collins St West, 1868.

‘Select evidence to select committee on Chinese Immigration’, V&P (Vic., L.C.), 1856-57, Vol. 2.

South Melbourne’s Heritage: An illustrated guide to the history and development of the city of South Melbourne, City of South Melbourne, Ministry for Planning and Environment, December 1988.

The Age, “The Chinese Question: Movement for Release from Quarantine”, 16th May 1888, p. 5.

The Argus, June 14th 1855, p. 8.

The Argus, February 26th 1859, p. 1.

The Argus, ‘Chinese Immigration’, 26th April 1855, p. 4.

The Argus, ‘Chinese Residence Tax’, 31st May 1859, p. 7.

The Argus, “Our Oriental Traders”, 14th April 1863, p. 5.

The Argus, ‘Police; City Court Thursday June 2nd’, June 3rd 1859, p.5.

The Argus, ‘Recruiting Stupidity: To The Editor Of The Argus’, 24th Janurary 1916, p.11.

The Argus, ‘The Duke of Edinburgh in Victoria: The Corporation Fancy Dress Ball’, 24th December 1867, p. 6.

The Argus, ‘The Famine In China’, 21st May 1878, p. 6.

The Argus, ‘The Late Mr. Kong Meng’, 24th October 1888, p. 16.

The Herald, “The Chinese In Victoria: Kong Meng”, 17th August 1863, p. 4.

The Leader, ‘Mr. Edwin Exon’, 4th June 1910, p. 22.

Yong, Ching Fatt, ‘Lowe Meng Kong (1831-1888)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 5, (MUP), 1974, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lowe-kong-meng-4043.

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm